Jonathan S. Mitchell

My research program is focused around using fossils and phylogenies to understand what shapes macroevolutionary dynamics. For my dissertation, I studied ecomorphology in living and extinct birds. Since then, I have worked on dinosaurs, salamanders, squirrels, swallows and many other groups. My primary research interests are in the composition of ancient communities, how we can model ecosystem change, how to adjust for the biases imposed by preservation, what level of certainty we can have regarding the ecology of extinct species, and how ecology shapes both within-lineage evolution and large-scale changes in clades.

I have done fieldwork in Argentina, Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming and North Carolina.

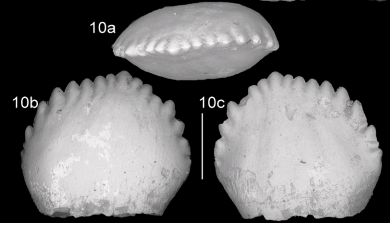

Microvertebrate bonebeds are diverse assemblages of extremely small vertebrate fossils. Often formed in channel lags or ancient ponds, they preserve small pieces of most of the vertebrates that lived in the area around the deposit. These deposits preserve everything from crocodile teeth, fish scales, mammal jaws, to dinosaur bones and bivalve shells, all jumbled up together and disarticulated. Most of my non-morphometric data come from such deposits, and most of my field work has focused on collecting, sifting and sorting these remains to get an idea of how diverse ancient ecosystems really were. Once we understand what organisms comprised a fossil assemblage, we can begin to apply ecological models to better understand how large scale biotic and abiotic changes rippled through communities.

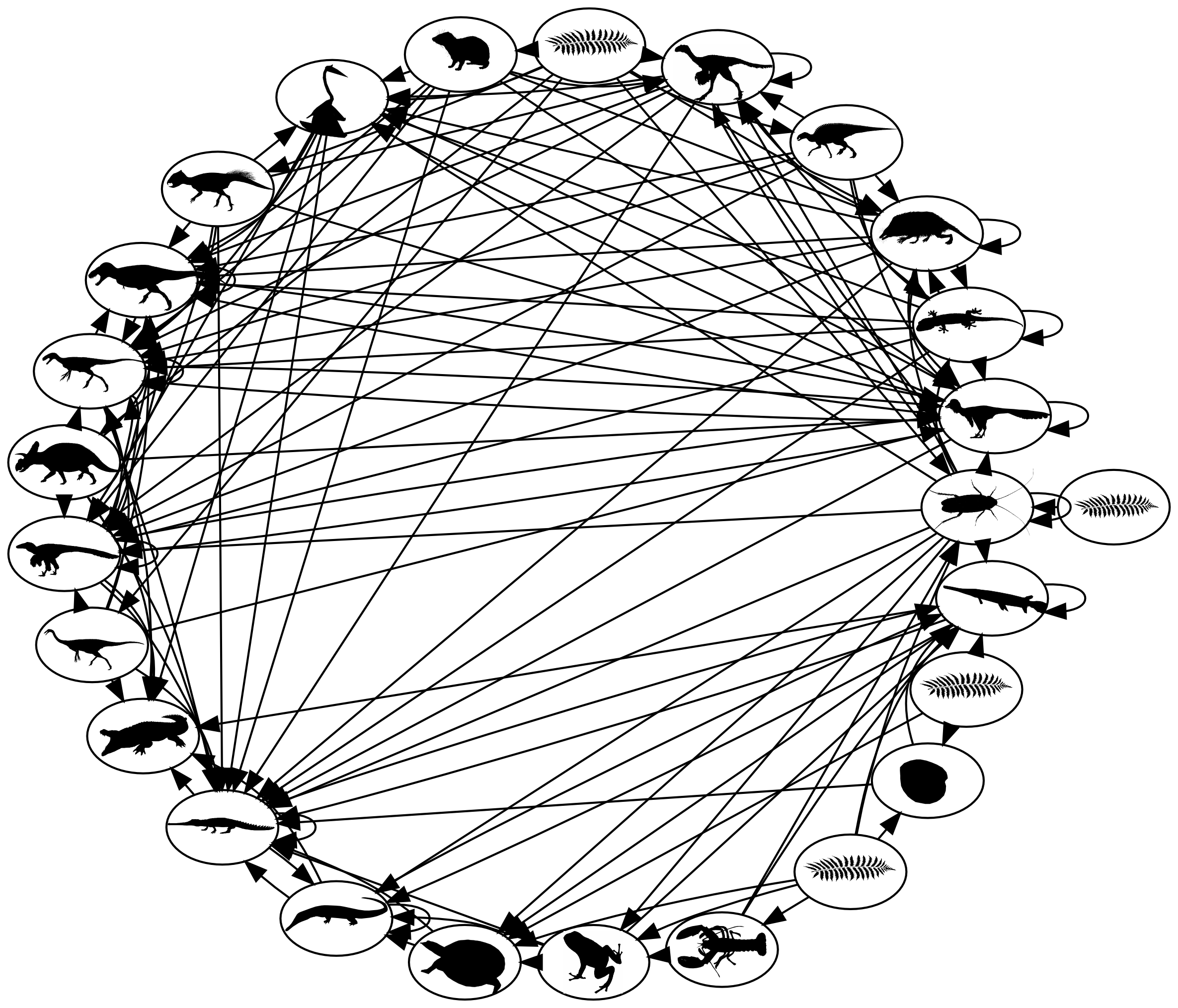

One of my major research interests is how ecosystem structure impacts macroevolutionary dynamics. Fossil ecosystems provide a ripe opportunity to examine how climatic fluctuations, mass extinction events, and the evolution of new clades impact community composition. Many ecological models, such as Bayesian Network food webs, try to predict extinction probabilities from fundamental measures of food web topology. However, without observed extinction data, they cannot be parameterized. Fossil ecosystems may have uncertain topologies, but they provide observable extinction events that can parameterize ecological models. By fitting ecological models to fossil data, we can learn more about ancient ecosystems and more about how ecological models function. It's a win for both ecologists and paleoecologists. The major sources of uncertainty in fossil food webs are: 1) how preservation biases our view of what organisms lived in a community, and 2) the ecology of the extinct species within the community.

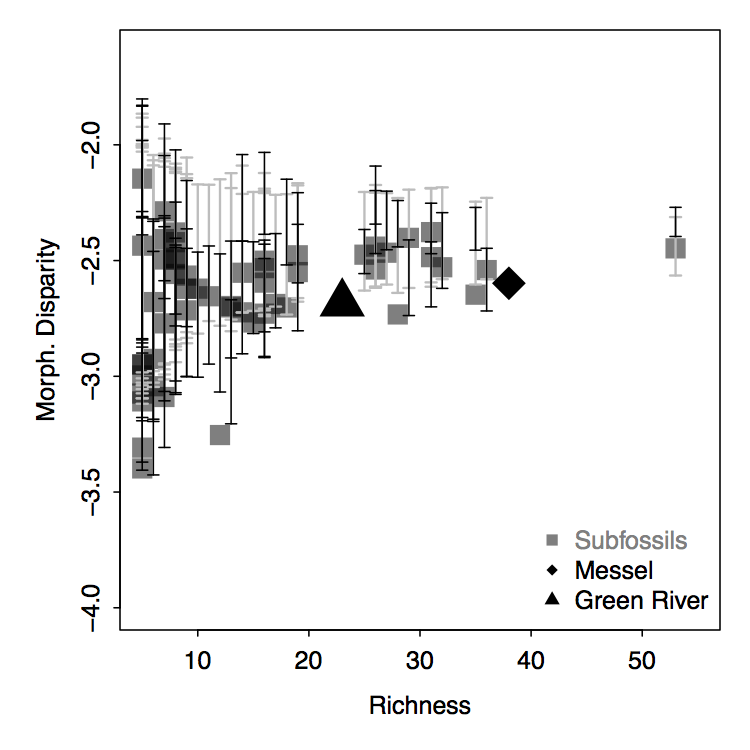

Preservation is not uniform among species. Some organisms are larger, or have more fossilizable hard-parts, or live in more preservable environments than others. This means that our view of the composition of an ancient ecosystem is inherently biased. We only know about the most preservable organisms that lived in the environment, and the most preservable organisms are an ecologically non-random subset of all of the species that made up an ancient community. However, the biases in preservation are fundamentally understandable. Traits that influence preservation can be measured, and we can model what sort of species are most likely truly absent from an ancient community (that is, what species would we expect to see based on preservation, but don't).

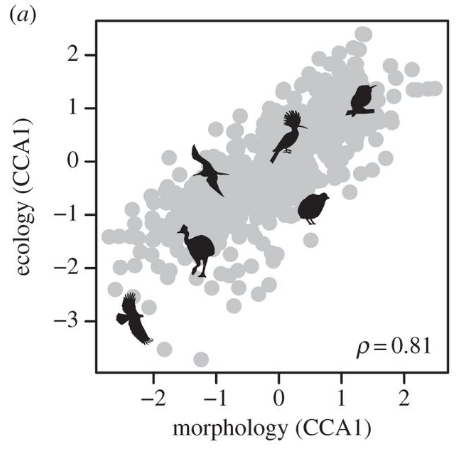

Extinct organisms cannot be tracked and observed to see how they foraged and what foods they ate. Understanding the ecology of extinct species requires building models to predict how ecology and morphology are related in extant taxa, and then applying these models to extinct species with known morphologies to predict their ecologies. But fossil specimens often preserve "extra" information like fossilized gut contents or stable isotope signatures of diet. By testing how well ecomorphological models predict this "extra" information, I have been working on assessing the uncertainty surrounding ecological reconstructions in extinct lineages.

Anagenetic, within-lineage, change is something that can be studied at both microevolutionary timescales and within the fossil record. Documenting how individual lineages become more or less specialized via morphometric measurements of individual specimens within successive deposits can provide insights into what shapes evolutionary trajectories.

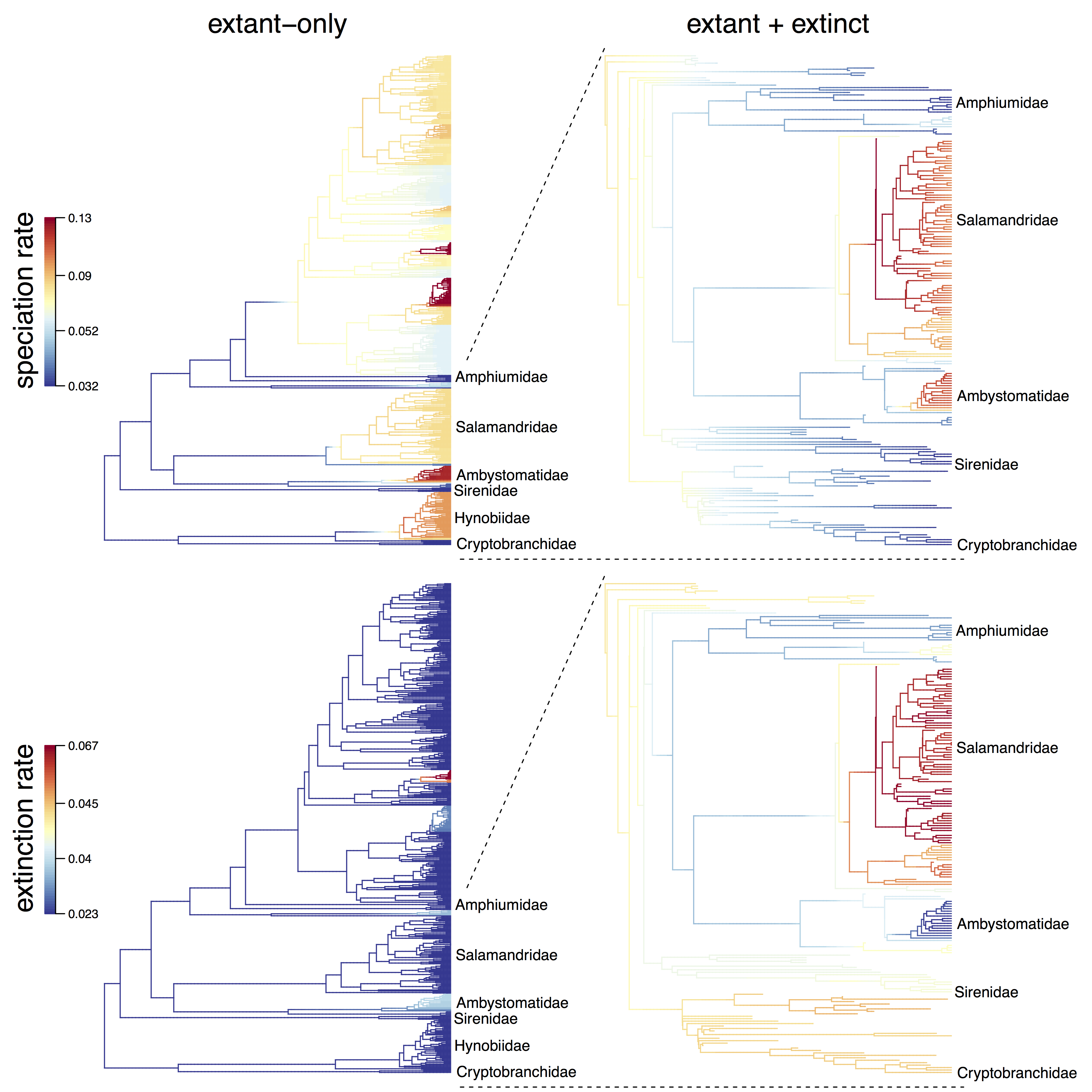

Rates of speciation, extinction and phenotypic evolution vary across lineages. Quantifying the role of ecology in shaping this variation requires synthesizing all of my research goals together: identifying the ecology of organisms, quantifying how ecology influences extinction, exploring trends within individual lineages, and combining data from extinct and extant species.